City of Peace and Justice? Not yet for all

What is MNOS?

MNOS is the Migrant Needs, Opportunities and Skills project, funded by The Hague municipality, which was completed in March 2022. The idea to ‘audit’ the situation in two deprived city neighbourhoods, Schilderswijk and Spoorwijk, was initially conceived by Dalmar Hamid Ali, herself a refugee researcher and ISS Migration track graduate. She is also MNOS Research Coordinator and led a team of 13 Migrant Researchers from September 2021 - March 2022. The team received invaluable support from the ISS project office.[1] This short overview relies on survey results with 152 respondents and on almost 100 interviews with migrant men and women, youth, professionals, volunteers and with employees of The Hague municipality carried out by the MNOS team. Of these interviews, almost 60 were conducted by Dalmar for a Baseline Study. The final report will be submitted in June 2022.

Den Haag municipality support

The municipality aimed to promote academic collaboration and gain insights into vital problems in the ‘City of Peace and Justice’.[2] This project was perfectly timed since it aimed to influence the city’s planning process and plans were being drawn up in 2021-22 in both selected areas of the city. With a relatively modest budget (€65,598) we managed to foster collaborations with local voluntary and public bodies, and between two Hague-based higher education institutions (through Helen Hintjens for ISS, and Naomi van Stapele, at The Hague University of Applied Sciences - THUAS). MNOS examined migrant poverty, the under-use of their talents and the need for more economic opportunities.[3] The Baseline Study outlined seven recommendations for The Hague municipality:

- Linking-up information through One-Stop-Shops

- Shaping alternative pathways towards decent work

- Securing well-being in the neighbourhoods

- Pathways for youth

- Opening up youth prospects

- Tackling long-term poverty and lack of opportunities

- Transforming the municipality’s vision of these neighbourhoods

These recommendations were discussed with Schilderswijk and Spoorwijk representatives and with a member of The Hague Neighbourhood Team in March 2022.[4] The discussions will continue in April and May, as neighbourhood plans are currently being finalized.

Background to MNOS

In 2020, as the pandemic hit, ISS funded four projects through the Local Engagement Fund (LEF 1). One was DUCCC (Documenting the Undocumented: Coping Creatively with COVID) which worked with eight migrant researchers and gathered over a hundred virtual artefacts (videos, music, photos, stories, blogs, poems) documenting the daily lives of undocumented people in The Hague through the first year of the pandemic. DUCCC contributed to an Open University (UK) project, COV-19: Chronicles from the Margins, run by Professor Marie Gillespie, an online archive including blogs, creative artwork, photo-stories and video from across the planet. MNOS can be seen as a spin-off of DUCCC, especially since several DUCCC researchers joined the MNOS Migrant Researcher team. Two local NGOs, Filmis and PRIME, provided valuable logistical support for both DUCCC and MNOS.[5]

Some results so far

From 2021-22 the Migrant Researcher team expanded from 8 to 13.[6] Their dedication and reflections on hardships experienced during the pandemic by migrants were informed by their training in survey methods, story-boarding and digital story-telling.[7] The survey was completed between October and December 2021, and from January to March 2022 the researchers gathered narratives of migrants’ life experiences.[8] Dalmar helped create a vibrant network of community groups and local organizations including men, women and youth groups in Schilderswijk and Spoorwijk. We thank STEK Wereldhuis, Lukaskerk, the Multicultureel Ontmoetings Centrum, Centrum de Brucht in Schilderswijk, and the Vadercentrum, Wijkcentrum de Wissel, the Dutch Refugee Council, the Centre for Children and Families (CJG), the Youth Intervention Team (JIT) and Wijkcentrum Parada of Spoorwijk for their support.

Among the key findings were the need for action to reduce the city’s internal polarization and create more post-pandemic opportunities for young people and single women-headed households. Migrant opportunities and skills were found to mostly depend on local policies, broader economic conditions and the human and financial resources available for training, education and work experience, especially of youth. Localized poverty and debt seem to be rising (See Box 1).

The survey suggested that The Hague municipality looks quite remote from a neighbourhood perspective. The Baseline Study also hints that even though some municipality programmes work quite well, more can be done to harness skills, including those of undocumented migrants. Legal status is a real divide between residents with migrant backgrounds. This growing divide poses risks for The Hague as a city. For those with legal status, more opportunities and possibilities exist when it comes to education, work and even healthcare. A Turkish-Dutch woman, studying at THUAS and working as a local volunteer, noted:

If you are living in the Netherlands and able to integrate, you can live a normal life and have a stable life. In general, you don’t need much because the municipality provides all that we need (Interview, woman respondent, Spoorwijk, August 2021).

Even those who have retired feel able to access education:

I am retired, a pensioner but I am also a PhD student and now I would also like to learn more about religion so I am in contact with the Academy of Amsterdam (Interview, Baseline Study, Congolese male respondent, Schilderswijk, July 2021).

Gaps are growing, however, between undocumented and other residents in these two neighbourhoods, which is aptly illustrated by a middle-aged Moroccan IT expert who speaks eight languages, yet can only find cleaning or decorating work:

…a secure, stable living, stable home and surety of a job…is not possible, as I am undocumented. There are opportunities but if you are considered to be an undocumented migrant all doors are closed (Interview, man respondent, Schilderswijk, July 2021).

These narratives depict the sheer precarity of everyday life for those who have so much to offer this city. Unlike migrant status holders, undocumented migrants’ lack of legal status, unstable work and problems with housing and education, impinge heavily on their well-being. There are also other risks involved in further criminalizing poorer neighbourhoods that may implicate wider Dutch society. The vital caring and community roles that undocumented people play in the city of The Hague should give them rights to everything this city has to offer so that they can live a decent, dignified life. One researcher in our team asked, ‘who is a migrant’? In a sense, we are all migrants, potentially, and each of us needs decent work, access to basic needs (housing, health, education) and recognition for what we contribute to society. Increasing opportunities and countering negative stereotyping in media and schools can help promote more equal life chances for all neighbourhoods in The Hague. We hope the municipality of The Hague will, in the future, reinvest in both of these ‘problem’ neighbourhoods by recognising the talents of those who live there and who play such a crucial part in the social and economic life of this city.

Conclusion: make true the name of this city

We hope the Baseline Study, survey and interview data, as well as our soon-to-be-completed final report, will help those responsible for finalizing neighbourhood plans in Schilderswijk and Spoorwijk to include the lived experiences, needs and aspirations of all local residents. The first priority is to engage with the broader debate in the Netherlands about tackling inequalities in cities, to reduce crime, poverty and despair. We advocate a politics of hope to overcome these divides and misperceptions of vital areas like the neighbourhoods in focus. At the neighbourhood, city and national level, all migrants’ needs and skills need attention, documented and undocumented. For migrant youth, especially, opportunities are needed to break social isolation, stigma and growing poverty. Our team is keen to encourage those working in the municipality of The Hague to regularly visit these neighbourhoods and hear from these migrants themselves about how to achieve more inclusive development at the local level. There are already numerous pathways to genuine social and economic inclusion instigated by migrant residents, such as those driven by voluntary initiatives that make true the name of this City of Peace and Justice.

Our litmus test for MNOS is to bring the priorities and insights from migrant residents themselves to the attention of the municipality of The Hague. Acknowledging their creativity and efforts at social inclusion, in both neighbourhoods, can be a first step towards building relationships of trust between the city authorities and local residents. This is a vital first step towards inclusive development.

Footnotes

- We would especially like to thank Claudia and Sharmini, Veronika and Eva for all their support.

- For a video (in Dutch) on neighbourhood planning see: here

- Throughout the MNOS preparation and implementation process, Dr Rachel Kurian, former ISS colleague, provided unstinting advice and support, informing us of municipal priorities and reassuring us that we were on the right track. Thanks to her for consistently boosting team members’ morale. Thanks also to Sylvia Bergh of THUAS, formerly of ISS, who ran a ‘sister’ project on the elderly and heatwaves in Den Haag. Sylvia helped us find Ashley, who did the survey training (see footnote 7 below).

- We are grateful to Renzo Steijvers, head of Schilderswijk neighbourhood office, Jorine Smits who newly joined the Laak/Spoorwijk neighbourhood team and Mohamed El Khalifi, of The Hague municipality Neighbourhood team for meeting with us and discussing so frankly.

- We are grateful to both FILMIS and PRIME for their on-going support in tracing the lives and resourcefulness of undocumented people through the pandemic. We especially thank Jack and Joy, Marijke Bijl and Ahmed Pouri for their timely advice and insights, and for their complete consistency.

- In alphabetical order we thank: Aileen, Alan, Arshad, Jack, Jemimah, Joy, Laina, Noriko, Rita, Taiwo, Tilak, Vicky, Victoria and Yasmine.

- Ashley Longman of THUAS was our trainer and advisor for the survey methods. We benefited from his long experience of designing and analysing surveys. This helped us to produce results which were visually converted into tables by Delphin Ntanyoma, recent PhD graduate from ISS. Story Boarding training was by Prue Thimbleby, a UK-based professional trainer and the Digital Story-telling workshop was run by Aglaya Jimenez. Thanks to all our trainers.

- We are indebted to the 152 migrant women and men (68 men, 79 women, 5 unspecified) who responded to our survey. All either lived or were involved in community groups and activities located in the two selected neighbourhoods.

Box 1: Overview of Survey Results

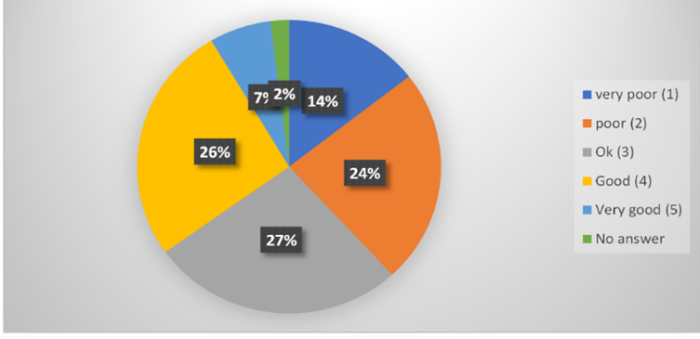

Table 1: Survey respondents’ perceptions of present quality of life

Note: percentages (total 152). For 65% the quality of life was poor, very poor or just OK.

Table 2: Communities of particular concern

Note: These were not the only communities of concern, but their quality of life was self-evaluated as significantly lower than on average in the survey.

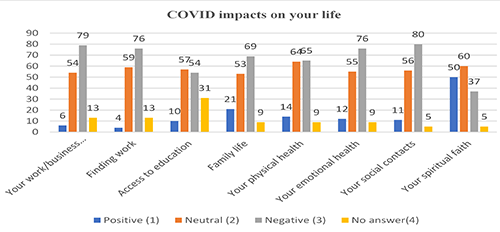

Table 3: Impacts of pandemic on aspects of life

Note: Interestingly, the only positive effects overall were for the spiritual dimension.

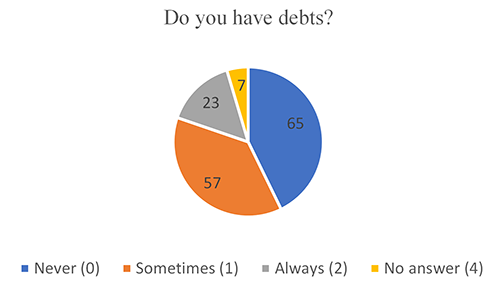

Table 4: Self-reported debt at the end of the month

Note: Figures are numbers, not percentages. Around 40% have no debt, and some of these may have reasonably good incomes. Some of those without debts did not borrow since their incomes were so low they knew they could not pay back money borrowed. Most undocumented people cannot borrow except from friends or family and cannot access municipal help for debt relief.

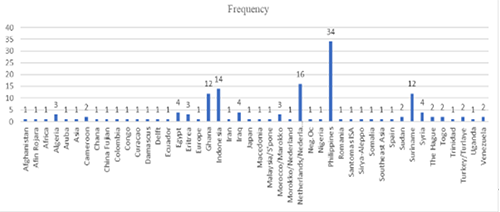

Table 5: Place of birth of survey respondents (open question)

Note: some responses are inconsistent, e.g., Syria should include responses Sirya-Aleppo and Damascus as well as Afin Rojava. Only one response was possible per survey respondent.

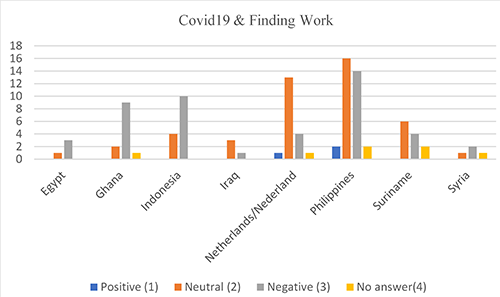

Table 6: Impact of pandemic on work: different origins

The differences between nationalities express some variation between migrant workers, integrated migrants with Dutch nationality and refugees from countries at war such as Iraq or Syria.

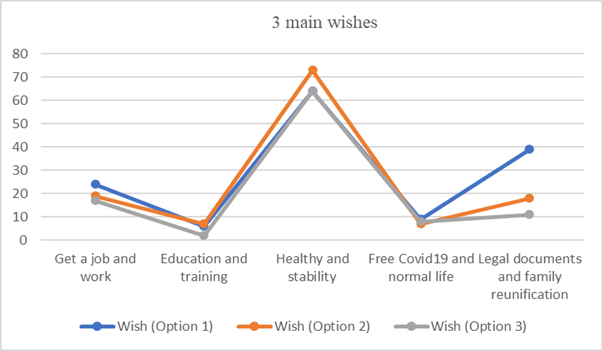

Table 7: Dreams 1, 2 and 3

Note: For around 40 (25%) of our 152 respondents, legal status was their greatest wish, even during the pandemic.

Box 2: Telling Tales: Extracts from Interviews

Alan (migrant researcher): Do you have any suggestions to how they could have helped you better?

Zoran (Kurdish refugee): I don’t know what the municipality here can do. I want to continue my sociology studies and apply it, but as you see I have no Dutch or English skills. The nearly two years that I spent isolated in the refugee camp have destroyed me. The last strength that I had left, was gone there. I could never have learned the language there. With all my traumatic experiences and psychological problems. You know what I have been through. I broke at some point. I couldn’t endure anymore their fascism and threats. Because of their constant meddling in my life I wasn’t able to live like a normal human. I guess the municipality or government or whatever should have helped me when I was in the camp. Yes, they say they don’t help people that haven’t received a residence permit yet, but that is nonsense. What are you expected to do in the whole time? Especially when you’re having so many difficulties.

Alan: If you got to make three wishes, what would they be and why?

Zoran: Of the municipality/government and such?

Alan: It can. In general.

Zoran: I would have wished that they’d actually asked me about my education. What I have done, want to do, or wish to learn. If they’d cared for me while I was in the camp, I’d be speaking now in Dutch and be a teacher of sociology at one of the schools here.

********************

Another individual was working from 5 am till after 10 pm seven days a week, both in the home and a shop, sending money home for her son and daughter. By the time she left that job, ran away from it, she was suffering from chronic sleeplessness and starving.

Jack: (migrant researcher): So, was this employer aware that you were undocumented when they hired you?

Jenny: (not real name): Yeah, actually they promised me that they would help me get a paper, because they had a shop so they could process my paper so I could be their sales lady or a cashier in their shop. I thought before that it was possible, that's why even [though] the work was hard I still managed to work every day for three months, but then after that it was so difficult for me because I was getting thinner and thinner, so I decided to run away and a friend of mine helped me.

Jack: How old were your children when you left them in the Philippines?

Jenny: My daughter was turning 7 and my son was 6 years old, so I’ve been here for 17 years already… Actually, my initial plan was only to stay here for five years to work, to really work hard and then save money and I go back home, but yeah, it's only wishful thinking. I thought I could do it, but then another year and then another year and another year until I have been here for 17 years. Because I'm also supporting my parents, because they're old and sometimes I also help my siblings; I have six siblings in the Philippines. So sometimes, I help them also when there's an emergency in their family so, yeah, that's why I until now I still don't have enough savings for me to go back for good to the Philippines.

*********************

Noriko (Migrant Researcher): It’s quite hard for you that you cannot legally stay here. But you are not allowed to...

Samuel (not real name): Definitely. For me, as a person it's, it’s, it’s hard psychologically, financially and emotionally. And of course, my family. And at the same time, I don't see the logic because I'm paying taxes, you know. I am here so for humanity reason I don't think it's good for the Netherlands to do that. Get what I mean? I mean, … you allow the person to stay but you don't allow them to work. Yeah. And economically, actually, it will affect them because what will happen to me [is that] I will resort to doing blackjob. They will not be able to collect tax from me then. So, I mean, I'm not doing that. But I don't actually see the logic.

City of Peace and Justice? Not yet for all

Helen Hintjens is Assistant Professor in Development and Social Justice

Naomi van Stapele is Lector Inclusive Education at The Hague University of Applied Sciences

Dalmar Hamid Ali is Visiting Fellow at ISS

Disclaimer

The views in this article are entirely those of the authors and not of the Gemeente which funded this study or of ISS.